Six winters ago, the Isle of Wight was buried in rare volumes of snow. Cars were abandoned and the island’s small stretch of dual carriageway blocked.

“From an emergency point of view, we were stuffed. Couldn’t get anywhere,” recalled Chris Smith, then head of ambulance. “I said to the medical director, ‘I have an idea. Let’s put clinicians into the control room.’” It meant 999 calls could be better prioritised, expert medical advice dispensed by telephone. “It changed the world for us,” said Smith.

Today that control room is one vast, physically integrated care hub attracting attention in the UK and internationally. Medical professionals from Canada, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, South Africa and more have visited to see if it can be replicated.

A busy room at St Mary’s hospital in Newport, it houses 999 emergency calls operators, NHS 111 call handlers, paramedic clinical advisers, a crisis response team, GP out-of-hours services, district nurses, mental health workers, social workers, pharmacists, the private pendant alarm company Wightcare, occupational therapists and the charity Age UK.

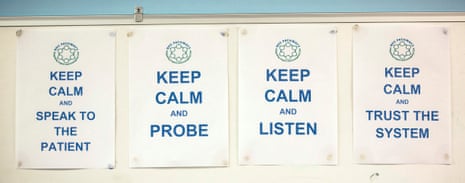

At this, the beating heart of the island’s emergency and unscheduled care system, health and adult social care sit side by side. Crucially, there are people from different bodies sitting within feet of each other and, more crucially, constantly talking. It allows instant access to the patient’s records from all those organisations. Tele health enables the remote monitoring of blood pressure, blood sugar or oxygen levels on patients linked up to computer equipment at home. There is CCTV. Patient transport. A pharmacy helpline.

Here, you would hope, it would be difficult to fall through the gaps.

Smith, 58, now clinical director who heads the hub, envisages further integration, knocking down even more silos around the different bodies and agencies responsible both for health and social care.

The phones ring constantly. Kim Boxall, a paramedic and clinical adviser, alerts A&E to a collapsed woman on her way by ambulance. Another 999 call is from someone worried about an elderly neighbour falling. Boxall speaks to Wightcare, and discovers it is one of their clients, so they are willing to be dispatched rather than an ambulance. Medication advice is required for another patient, which she passes to Margaret Chan, the pharmacist on the next desk.

A few rows down Sandy Cummins, a social worker attached to the crisis response team, is preparing to visit a man in his 90s who was seen by paramedics after he fell and injured his head. A team discussion takes place. “The paramedic has checked him over, so he is safe to be at home. He cooks his own meals, his family contact him, but by phone because they are not on the island. He’s typical,” she said.

The job of the crisis response team – district nurses, coronary care nurses, clinical assessors, paramedics, an occupational therapist, social worker and Age UK representative – is to wrap 72 hours of care around such cases, and they have four hours to respond to each referral.

The point is to keep people out of hospital, the last place where elderly, vulnerable patients will want to be. People such as Bob (not his real name), who is 92 and suffers from dementia. After his wife and carer, Flo, died of a stroke at home, the normal practice would have been to take him to hospital in the same ambulance as her body. He would then most likely have been admitted as a social care admission until a care package was set up. Instead, the crisis team moved in within half an hour of the ambulance call, organised a weekend in a residential home, set up a complete care and support package, and within two days he was back home, where he remains today.

Since April 2015, the crisis team has seen 489 people, and it is claimed it has spent an estimated £725,000 less than it would have done with a more traditional approach. Of those 489 people, just 58 were admitted to hospital, mostly due to complications of existing long-term conditions.

Solutions found are not always the most obvious. A blind man in his 90s wanted to remain at home after his wife and carer collapsed and died, but worried he could not care for his two cats. Rather than taking him into hospital, where he was at risk of infection, the crisis team were immediately at his door. They liaised with social services and Age UK. A tradesman was found to fit a complete cat ecosystem, including a cat flap he could easily hear and special feeding system he could manage.

The hub is just one cog in the island’s My Life a Full Life (MLAFL), an overarching programme – one of the Vanguard new care models – focusing on older people, and those with long-term conditions and mental health needs, bringing the NHS trust, the local authority, the clinical commissioning group plus the voluntary and private sector together to deliver a vision for integrated care and support.

Such integration is perhaps easier because the island, through physical necessity, has been doing it for years. It already had the only combined hospital, ambulance, community and mental health services in England, serving a population of 140,000, and has one local authority.

It sees its single point of access integration programme as radical and innovative. Steve Stubbings, deputy council leader with responsibility for adult social care, said the ultimate aim was the “Island of Wight pound”, “a joint, pooled budget”, where money from the trust and the council gets put in the same pot. “It is definitely do-able, within the next 18 months,” said Stubbings.

The island’s proportion of over-85s is significantly higher than average and projected to grow by 20% in the next decade. It has the highest recorded crude rate prevalence of dementia in the UK. Social isolation among elderly people who have lost a partner and have families living on the mainland is a major issue. “The train has landed at our station probably 10 or 20 years before the mainland,” said Smith.

But it has a wealth of active retiree volunteers. Key to MLAFL is tapping into the very strong third sector. Lee Hodgson, chief executive of the island’s Citizens Advice, is also managing director of Isle Help, an organisation pulling together under one physical roof Citizens Advice, Age UK, the Law Centre, the independent living NGO People Matter and fuel poverty charity the Footprint Trust. Clients tell their story just once through Isle Help’s digital referral system.

It has a legal partnership, and shares resources, with the local authority – the first of its kind, he said, between the third sector and a statutory body – and is a model for the NHS trust and CCG “on how they can work better with the third sector”.

The integrated model is dependent on this third sector and also private fundraisers such as Aaron Rolf and Gemma Blamire, who have raised thousands since the death of their six-year-old daughter, Sophie, in 2013 from an inoperable brain tumour. Their Kissypuppy charity has ensured the island’s Earl Mountbatten hospice now has facilities for dying children, where no such facilities on the island existed previously. It also facilitates visits from schools, to help remove the taboos around dying.

In keeping with the integration theme, the hospice now works with the NHS and social services, with its workers moving in to take those who have recently died out of hospital within four hours. It is all part of the community pulling together, said Rolf. “It is common sense all these services should be talking. The hospice should be talking to the NHS and the NHS shouldn’t be precious about the care they give. We are not always going to agree, but it is having that conversation. We like to think that Sophie got everybody talking,” he said.

Through MLAFL, the island’s health, social care and the voluntary sector are integrating in three distinct areas, each with a dementia-friendly health and wellbeing centre. One GP, Dr Cabrini Salter, envisages a future where the voluntary sector “could do some of the healthcare that was traditionally the role of doctor or nurse”.

“Certainly, we are considering how volunteers could give insulin injection. We are not quite there yet but we are working at how to do it safely,” she said. Another area being explored is volunteers in care homes helping patients with exercises to get them moving again after a fall, which can be time-consuming for pressed staff.

Karen Baker, chief executive of the Isle of Wight NHS trust, believes their system could be replicated. The trust is now aiming to develop a tool kit to help others. “People worry a lot about their organisational boundaries, and their allegiance to their trust or council. Somehow, it is about cutting through that without having a massive reorganisation of the NHS,” she said.

She added: “It is about concentrating on people rather than organisational structures. In that hub, there is no reason you should know whether they work for the NHS trust, the local authority, or private employers. They are all in this room together, from different places, concentrating on what is the best thing for the person.”